In the book " The United States Cavalry: An Illustrated History, 1776-1944, Gregory Irwin wrote: "Davis's Valiant Coup compared favorably with anything Stuart had ever done, and it stands as an unrecognized omen of what was to come." Yet 158 years later this amazing accomplishment is still overshadowed by the magnitude of the losses when the Union Garrison surrendered at Harpers Ferry, Virginia on the morning of September 15, 1862 as well the losses at Antietam on September 17, 1862, and seems, to some extent, to have been relegated to the position of a footnote in the study of the Maryland Campaign. Maybe it is time to explore this subject once again and bring it out of darkness into the light.

What is the "Coup" Irwin refers to anyway? It is described below.

On the evening of September 14, 1862 the approximately 14,000 United States soldiers of all arms who made up the federal garrison at Harpers Ferry were surrounded on all sides by a much larger force of Confederates under the overall command of Major General Thomas J. Jackson. They were "trapped" in an indefensible town with no hope of escape. An ignominious surrender seemed inevitable. Or so it seemed.

At least one man in the town, Colonel Benjamin Franklin Davis, commander of the Eighth New York Volunteer Cavalry, had different ideas, however. He had no intention of throwing in the towel. He was reportedly overheard telling the commanding officer of the garrison, Colonel Dixon S. Miles, a regular army officer he had know since 1856 when both were stationed at Fort Fillmore, New Mexico Territory, that "he would never surrender his force to a living person without a fight." As early as the afternoon of September 13, after Maryland Heights had been evacuated, he "was busy, for he was going to take his regiment out, and not stay there and be gobbled up by the rebels without making an effort to get away." He was actively engaged in getting support for and making arrangements to cut his way out. "To be compelled to surrender without a fight was not Colonel Davis's purpose." The colonel’s education, training, experience, natural aggressiveness and bravery made the thought of surrender totally repugnant to him. He was “tough, daring and resourceful” and was not about to wind up in some Confederate prison if he could help it.

Colonel Benjamin Davis, nicknamed "Grimes" by his West Point classmates had not come to Harpers Ferry to surrender and had no intentions of doing so. He consulted with at least some if not all of the other commanders of the six cavalry regiments at Harpers Ferry. They agreed they should make an attempt to get out of the beleaguered town. Davis then went to speak with Miles, and implored him to a give his permission for the movement noting "the horses and equipment would be of great value to the enemy if captured, and that an attempt to reach McClellan ought therefore to be made". Miles was reluctant to do so at first but finally late on the afternoon of September 14, he gave his permission for the attempted breakout, in hopes the cavalry might be able to reach George B. McClellan's Army, which was known to be in Maryland, and that he would come to the garrisons rescue before it was to late.

Once a decision had been made Colonel Miles had his Assistant Adjutant General, Lieutenant H. C. Reynold draft the orders for the cavalry to leave Harpers Ferry.

Headquarters,

Harpers Ferry, Va., 14 Sept., 1862

SPECIAL ORDERS No.120.

1st. - The cavalry forces at this post, except detached orderlies, will make immediate preparations to leave here at eight o’clock tonight, without baggage, wagons, ambulances or lead horses; crossing the Potomac over the pontoon bridge, and taking the Sharpsburg Road.

2nd. - The senior officer, Colonel Voss, will assume command of the whole; which will form in the following order: the right at the Quartermaster’s Office; the left up Shenandoah Street, without noise or loud command, in the following order: Cole’s Cavalry, Twelfth Illinois Cavalry, Eighth New York Cavalry, Seventh Squadron Rhode Island Cavalry and First Maryland Cavalry. No other instructions can be given to the Commander for his guidance than to force his way through the enemy’s lines and join our own army.

By order of Colonel Miles,

H. C. Reynolds,Lieutenant and A.A.G.

Once the orders had been issued cavalry commanders went to their respective regiment to inform the rank and file of the decision. When the Seventh Rhode Island heard the news about four o’clock Major Corliss also reportedly told his men that by the “next morning they would either be in “Pennsylvania, or in hell, or on the way to Richmond.” In some case’s men were given the option of staying at Harpers Ferry when the rest of the regiment left. There is no evidence well, able bodied men with a fit horse chose to stay however. The soldiers quickly prepared to leave Harpers Ferry. Horses were groomed and fed what forage was available and led to water. Saddle girths were checked. The men discarded all non-essential items including, tents, overcoats, blankets, extra paraphernalia and accouterments. They were issued extra ammunition. They might have eaten what food they had available and filled their canteens with water.

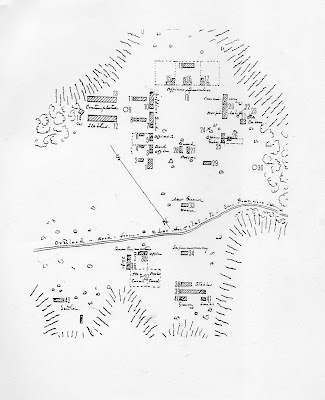

The individual regiments began to gather at the rendezvous point on Shenandoah Street around 8 o’clock at night. Some of the troops probably also lined up on Potomac Street. By then it was dark. Commanders whispered last minute instructions to their men. Henry Norton wrote “We were drawn up in line, and our sutler, knowing that he could not get out with his goods, went down the line and gave the boys what tobacco he had. Before we crossed the pontoon bridge each captain gave orders to his company that each man must follow his file leader and that no other orders would be given.

Each regiment formed in a column by two’s, in the order specified by Mile’s Special Orders 120. They began walking across the bridge, between 8:00 and 8:30 p.m., behind at least two guides who knew the country well. One of the guides was Second Lieutenant Hanson T. C. Green of Company A, Cole’s Cavalry, who had been seriously wounded at Leesburg on September 2, “when he was struck a crushing blow to the face with the butt end of a large army revolver, and across the head with a sabre.” Another guide was Thomas Noakes of Martinsburg, Virginia who had been employed for some time as a guide and scout by Major General Nathanial P. Banks and others. Noakes was reportedly “tall and athletic, brave and cruel, a Spartan in his indifference to physical comfort…a man of great prowess, and a valuable adjunct to the brigade.” Some participants noted that Colonel B. F. Davis and Lt. Colonel Hasbrouck Davis, of the Twelfth Illinois Cavalry were in the advance directly behind the guides. They were followed by the squadron of Cole’s Cavalry, some of whom had lashed their sabers to their saddles in an attempt to reduce the noise they made.

The rushing water of the Potomac and the sod and dirt placed on the bridge’s wooden planking helped muffle the sound of the horse’s hooves as the cavalry crossed the span. When the head of the column reached the Maryland shore they turned left onto the “Harpers Ferry-Sharpsburg Road”, also referred to as “the John Brown Road” that ran between the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Towpath and the bluff at the base of Maryland Heights and spurred their horse to a gallop. The column was well spread out as it moved northward in the inky darkness. It took almost two hours for the group of horsemen to cross the Potomac. Captain William H. Grafflin of the First Maryland Cavalry, who brought up the rear, testified before the Harpers Ferry Commission that he did not start crossing the river until about 10:30 p.m.

One mishap occurred aa the column crossed into Maryland. Some men from Company D of the Twelfth Illinois turned to the right toward Sandy Hook after getting across the Potomac. They quickly discovered their error and turned around after being fired upon by a few Confederate pickets. It is unclear if they all rejoined the rest of the column or if some re-crossed the pontoon bridge back into Harpers Ferry which they probably could not have done until the main column was all across.

Not long after crossing the river the lead elements of the main column also encountered a few Confederate pickets, from the 13th Mississippi Infantry of Brigadier General William Barksdale’s Brigade, which had been left on Maryland Heights with two Parrott rifles when Lafayette McLaws pulled the rest of his command off the hilltop and took them to Pleasant Valley to confront the Union 6th Corps which was in his rear. Thomas Bell wrote “after a spirited response from Lieutenant Green, in which the enemy retreated up the road to Maryland Heights, the column was under full headway.” Another member of the Eighth New York wrote in a letter to his father “we came to the rebel pickets and they were so scart (scared) they could not fire so we bound and gagged them and on we went. We passed within 80 rods of their cannon on both sides of us but they had no idea of our trying to escape and we rode by safe.

The column followed the Harpers Ferry - Sharpsburg road along the river for about a mile. While doing so they tried forming up as rapidly as possible by four, which was probably easier said than done. The road then took a sharp turn to the right and a steep climb up to the top of the Maryland Heights. One soldier noted the climb was so steep “that he had to grasp the mane of his horse to stay safe”. The column quickly became strung out. Henry Norton wrote “the only way we could tell how far we were from our file leaders was by the horses shoes striking against the stones in the road. Sometimes we would be twenty yards from our file leaders, and then we would come up full drive; then we would hear some swearing. That was the way we went for several miles”, sometimes on the road and other times across fields and open country. Thomas Bell also noted “the increasing pace of the head of the column making it difficult for those in the rear to retain their proper intervals. Until we reached Sharpsburg it was everyman for himself. The only clew was the clatter of hooves” and the rattle of sabers. “To those in the rear of the column the direction of these sounds was not easy to determine”.

At the intersection of the Harpers Ferry – Sharpsburg Road and the Lime Kiln Road the column veered to the left and at times followed the route of the Lime Kiln Road toward Antietam Iron Works. When not on the roads the column went “across, flats, over fences and through creeks.” At the iron works the horsemen crossed the Antietam, not far upstream of its confluence with the Potomac and then took the Harpers Ferry – Sharpsburg Road again, northward toward Sharpsburg. The head of the column arrived at the outskirts of the town around midnight. Campfires helped the men avoid the bivouacs of the Confederates that had retreated from South Mountain late on the 14th. Norton reported “at Sharpsburg, the advance made a halt for about half an hour, so we could close up and let our horses get their wind.

On nearing Sharpsburg, and thinking they might be in the vicinity of the Army of the Potomac orders were given to reply to any challenge that might be made. William Luffs of the Twelfth Illinois wrote, “the night had now become starlight, and as we approached the town, several cavalry vedettes were discovered in the road. To the challenge, “Who comes there?” the answer was “Friends of the Union.” This reply was unsatisfactory for the pickets fired upon the column. But without effect. A charge was ordered and promptly executed, driving the pickets in and through the principal street of Sharpsburg on the road toward Hagerstown.

As the Union cavalry headed northward out of Sharpsburg on the Hagerstown Pike the glow of campfires could be seen in the distance. Sounds carried through the night air including the loud voices of officers giving orders and the dull rumbling of wagon and limber wheels against the roadway, which indicated enemy camps could be nearby. “A civilian informed an officer of the 8th New York that the column was going right into Lee’s Army”. In actuality, Colonel Henry L. Benning’s Confederate Infantry of Brigadier General Robert Toombs Brigade and the Army of Northern Virginia’s reserve artillery under Brigadier General William N. Pendleton were both moving southward on the Hagerstown Pike toward Sharpsburg during the early morning hours of September 15 as the Union forces traveled north. The regimental officers and guides stopped the column to discuss the situation. The guides selected an alternate route, “a circuitous path through the lanes and by-roads, woods and fields” to the north and west of the Hagerstown Pike. The column marched steadily and silently threading their way between the camps of the foe” until it emerged at a point on the Boonsboro-Williamsport turnpike about two miles east of Williamsport. While Colonel Voss remained the titular commander of the cavalry column it is pretty evident by this time that Grimes Davis had assumed tactical command of the same and “took charge when trouble loomed”.

William Luffs of the Twelfth Illinois noted, “It was now just in the gray of morning. Fires of a large camp of the enemy could be seen, near Williamsport.” Henry Norton wrote, “just before we got to the pike we halted in a piece of woods. As the advance of the column approached the pike the rumbling of wheels in the distance toward Hagerstown was heard. Colonel (Davis) went ahead to reconnoiter, and when he got to the road, he soon found out it was a rebel wagon train principally loaded with ammunition and escorted by infantry with a detachment of cavalry in the rear.” The ordnance train was commanded by “London-born” First Lieutenant Francis W. Dawson, who was an assistant ordnance officer with Longstreet’s command. “It was an anxious moment, but Colonel (B. F.) Davis of the 8th New York and Lt. Colonel (Hasbrouck) Davis of the 12th Illinois, who were at the head of the column, were equal to the occasion.” The Eighth New York was immediately formed in line facing the road on the north side, the Twelfth Illinois in the same order south of the road, the Maryland and Rhode Island Cavalry were held in reserve; while Colonel Davis with a squadron of his regiment, advanced and took possession of the road so as to intercept the enemy. “All was done in silence, and it was still too dark for our troops, concealed in the timber which skirted the road to be seen”. The concealed Union horsemen watched Dawson and a small body of cavalry appear over a hill that rose to their right, followed by the ordnance wagons. As Dawson and the other unsuspecting Confederates rode toward the concealed Union troopers Colonel Davis reportedly quietly told his command “don’t shoot boys”.

“When the head of the train came up” Colonel Davis ordered it to halt, which it did without a shot being fired.” Dawson later wrote “the gloss was not yet off my uniform, and I could not suppose that such a command, shouted with a big oath, was intended for me.” When the command was repeated Dawson road forward and found himself at the entrance of a narrow lane which was filled with men on horseback. He could not tell if they were friend or foe in the predawn darkness. He confronted the Union cavalryman who he thought had ordered him to stop. “How dare you halt an officer in this manner. The trooper responded surrender and dismount. You are my prisoner.” When Dawson asked who he was speaking to the cavalryman reportedly answered, “Colonel B. F. Davis, 8th New York Cavalry.” Colonel Davis then ordered Captain William Frisbie, Company D, Eighth New York to take the train, “turn it right on the turnpike that ran to Greencastle, Pennsylvania and run it through to that place at the rate of eight miles per hour”. Frisbie purportedly “innocently” asked Colonel Davis where the road was, “and he was peremptorily ordered to “find it, and be off, without delay”.

Charles D. Grace described the capture of Longstreet’s train from the Confederate perspective in an October 16, 1897 letter to Ezra Carmen head of the Antietam Battlefield Board. He wrote, “If I remember correctly there were no guard for Longstreet’s train. The only guard, if guard at all were the details sent back to cook rations and a few on the sick list. We passed through Hagerstown and were nearing Williamsport about half past four o’clock a.m., on the 15th. The moon would occasionally show itself brilliantly through the drifting clouds. At a point about a mile east of Williamsport at a knoll of timber on the south side of the pike a road supposed to be the river road intersected the pike at right angles. The knoll on which the timber stood had been graded down to the west side to a level with the pike. To the west as far as the river or Williamsport was cleared land. As I came up to the junction of the road I found the men stopping and noticing some cavalry back behind the knoll, perfectly concealed from view, approaching from the east. I demanded to know by what authority the men were halted – the train still moving on – when two or three cavalrymen threw their guns down on me, saying “by this authority” their barrels glistening brightly. I replied that authority was sufficient. Just at that moment Colonel B. F. Davis came up, his horse on the gallop, his pistol in his right hand and in a perpendicular position above his shoulder, remarking to the men, “stand fast men and we will cabbage a hell of a lot of them.” I said being a little petulant. “Yes sir, I hope you will have them do so for General Jeb Stuart will have you in our condition in a few minutes as he is on his way this side of Hagerstown. The remark was either fortunate or unfortunate because he immediately ordered the men to throw down the rail fence on the west side of the road, at the same time ordering the prisoners, who numbered sixty-one, to move out and get in the wagons, which they did of course, and as soon as the prisoners were in the wagons Colonel Davis ordered four men to ride up by each team. As soon as everything was ready, the order was given to move off as fast as the teams could be made to travel”.

Elements of the First Virginia Cavalry harassed the rear of the Union column and it’s captured wagon train as it sped toward Greencastle. The Union rear guard was able to fend them off. The Virginians were not able to recapture any of the wagons or prisoners or inflict any casualties on the jaded Union horsemen. The command with their prisoners and captured wagons reached Greencastle about 9:00 a.m., on the 15th after riding fifty miles in twelve hours. The exhausted, hungry cavalrymen were warmly welcomed by the town residents, who plied them with every type of food imaginable. A trooper from the Fifteenth Pennsylvania Cavalry, who was in town when the column arrived wrote, “I saw the dusty procession marching into Greencastle, and had the honor of being placed, loaded revolver in hand, on the hind seat of an omnibus, to stand guard over the rebel prisoners, whom I conducted to the county jail”.

Not long after the Union Cavalry column arrived in Franklin County, Pennsylvania, the news was telegraphed to Harrisburg and Baltimore. The first telegram announcing the columns arrival in Pennsylvania was dated 8:00 a.m., from Greencastle. It noted “sixteen hundred of our cavalry are coming into town – they cut their way out from the neighborhood of Harpers Ferry”. At 9:00 a.m., Governor Curtin, who was in Harrisburg, telegraphed a message to Edward M. Stanton the Secretary of War; “United States Cavalry, from Harpers Ferry, has arrived at Greencastle, under command of Colonel Davis, Eighth New York. The force is 1,300 strong. They left Harpers Ferry at 9 o’clock last evening. One mile from Williamsport, they captured Longstreet’s ordinance train, comprising 40 wagons; also brought in 40 prisoners. Fighting has been going on for two days at Harpers Ferry. Colonel Davis says he thinks Colonel Miles will surrender this morning. Colonel Miles desires his condition made known to the War Department.

The breakout of the Union Cavalry from the surrounded town of Harpers Ferry on September 14, 1862 succeeded beyond anyone’s wildest dreams. It compares favorably with Nathan Bedford Forrest’s breakout from Fort Donelson with his Confederate Cavalry, prior to the forts surrender, in February 1862. While there is no question according to Special Order 120, that Colonel Davis was not in “official” command of the cavalry expedition, at least on paper, there is ample evidence that he had a great deal to do with initiating the idea and persuading Colonel Miles to allow the column to depart. In route he was instrumental in helping ensure the success of the venture and in the capture of Longstreet’s train. William H. Nichols of the Seventh Rhode Island would pen words that were reiterated by many others authors and army officers after the successful breakout. Nichols noted, “much of the success of the expedition was due to Colonel B. F. Davis of the Eighth New York Cavalry” who was afterwards recommended by Major General McClellan, for the brevet of Major in the regular army for “conspicuous conduct in the management of the withdrawal of the cavalry from Harpers Ferry”. In a September 23, 1862 telegram to Major General Henry Halleck, General-in-Chief of the United States Army, McClellan wrote, Captain B. F. Davis merits the notice of the government. I recommend him for the brevet of major. The honorary rank was confirmed to date from September 15, 1862.

It is unclear what the losses were in the ranks of the cavalry regiments that broke out of Harpers Ferry on September 14th, 1862, although the Eighth New York regimental history reported an enlisted man missing at Williamsport of the 15th. Some men were “lost” in route but many reportedly eventually rejoined their commands. A number of soldiers stayed in Harpers Ferry, either because they were sick or because they did not have a serviceable horse. The official records indicate the Twelfth Illinois reported two enlisted men wounded and four officers and 153 enlisted men missing. The Eighth New York’s casualties included 5 officers and 87 men missing. The First Maryland Cavalry lost 23 men when Miles surrendered. The men captured at Harpers Ferry were paroled. Many, including eighty members of the Eighth New York, wound up at Camp Douglas in Chicago, Illinois where they remained until they were exchanged in late November 1862.

Stonewall Jackson was deeply disappointed when he arrived in Harpers Ferry on September 15, to find the Union Cavalry gone. The New York Daily Herald reported on September 18, 1862, “His first question, after glancing over the eight thousand infantry drawn up unarmed in line before him, was, “where is all the cavalry you had”? And on being informed that they had escaped the previous night, en masse, he was silent, but his face, and the countenance of the rebels about him, wore a look of disappointment and chagrin.” He purportedly cried, impossible! I would rather have had them than anything else in this place.” James Ewell Brown Stuart was no happier than Jackson, in part, because he had admonished Lafayette McLaws to watch the Harpers Ferry-Sharpsburg Road. Captain William Blackford, a member of Stuarts staff wrote,” To think of all the fine horses they carried off, the saddles, revolvers, and carbines of the best kind, and the spurs, all of which would have fallen to our share, and the very thing we so much needed, was enough to vex a saint”.

In his September 21, 1862 report to President Jefferson Davis, General Robert E. Lee would play down the escape of the Union Cavalry from Harpers Ferry and the loss of Longstreet’s wagons when he wrote “unfortunately on September 14, the enemy cavalry at Harper’s Ferry evaded our forces, crossed the Potomac into Maryland, passed up through Sharpsburg, where they encountered our pickets, and intercepted on their line of retreat General Longstreet’s train. Some historians contend the loss of Longstreet’s ammunition had an adverse impact on Lee’s forces during the Battle of Antietam. The enemy captured and destroyed forty-five wagons.” Lt. Colonel Edward Porter Alexander, Chief of Ordnance for the Army of Northern Virginia would later write “the loss of forty-five wagons” loaded with ammunition and subsistence” had been a severe blow at such a distance from our base at Culpeper, Virginia. “On the 16th I was ordered to collect all empty wagons and go to Harpers Ferry and take charge of the surrendered ammunition; bringing back to Sharpsburg all suiting our calibres”.

Portions of this blog are extracted from the draft of a biography about Benjamin F Davis that is in in the process of being written by your truly titled "An Ornament to His Country". The source document from which this is extracted is copiously footnoted. Stay tuned!